Can you guess which novel the following beginning comes from?

Mr. and Mrs. Dursley, of number four, Privet Drive, were proud to say that they were perfectly normal, thank you very much. They were the last people you’d expect to be involved in anything strange or mysterious, because they just didn’t hold with such nonsense.

Mr. Dursley was the director of a firm called Grunnings, which made drills. He was a big, beefy man with hardly any neck, although he did have a very large mustache. Mrs. Dursley was thin and blonde and had nearly twice the usual amount of neck, which came in very useful as she spent so much of her time craning over garden fences, spying on the neighbors. The Dursleys had a small son called Dudley and in their opinion there was no finer boy anywhere.

Yes, it’s the first page of Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, J.K. Rowling’s breakout novel.

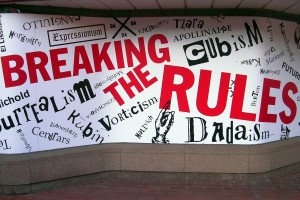

It’s a breakout novel in more ways than one, because in the process she broke a few rules, too:

-

Start with a problem: There’s no problem here. Everything’s “normal.” In fact, she drones on at length about how normal everything is.

-

Avoid the verb “to be”: She relies on the verb “to be” seven times in these two paragraphs, at least once in every single sentence.

-

Show, don’t tell: There is no action here, and therefore, no plot. This segment is merely a description, and not a very engaging one at that. In other words, she’s told us here about the Dursley’s, rather than showing us Harry, the main character. And speaking of which…

-

Start with the main character: She doesn’t even get to Harry until page 5. The first time I read this, I thought Dudley was the protagonist.

According to the experts, these are signs that your manuscript “needs work,” and you’ll never get it accepted by a publisher. But when these same experts analyze Harry Potter, they take a different tack. They tell you to follow the rules, because you don’t yet know how to break them. Once you become good enough, they say, then you can break the rules with impunity, like J.K. Rowling.

Or in the words of Randy Ingermanson, “This is ‘Telling.’ But it’s brilliant… Since it’s brilliant, there’s just no good reason to ‘Show’ it—unless you can ‘Show’ it better.”

Er… But I thought that “showing” was always “better” than “telling.”

In reality:

-

Showing is not always better than telling. You should show those things that are core to the story—the most interesting bits—and tell (i.e., gloss over) everything else.

-

A story does always start better with showing—the interesting bits—rather than telling.

-

This Harry Potter beginning sucks. But the book as a whole was good enough for Rowling’s audience in order to garner word of mouth, so that she could build up a fan-base.

-

That marketing feat is a significant achievement, and we don’t have to heroify Rowling in order to give her credit where credit is due.

-

There are precious few hard-and-fast rules, because beauty is in the eye of the beholder. There is no “better”; there’s only “better for me.” The rules, such as they are, ought to serve you, not to bind you.

-

Rich and famous authors don’t necessarily write “better” than you do.

-

If you want to become rich and famous, the quality of your marketing is more important that the quality of your writing. Or more precisely, the quality of your writing is measured by and controlled by your marketing. And that is what agents and editors are really arguing with you over, how well they think your manuscript appeals to their market, not over how “good” your writing is.

Keep writing!

-TimK

Leave a Reply