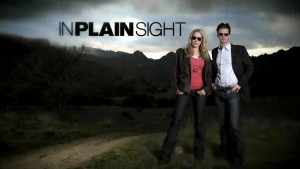

If 90% of everything is crap, that rule certainly applies to television. Most of what I see of current television series leaves me woefully unsatisfied, and even a little pissed off. Then, this past weekend, my parents introduced me to In Plain Sight, a show that a friend of mine called “a mid-grade crime procedural.” Interesting take, as I had a significantly more positive reaction.

I’ve only just gotten through season 1 and into season 2 on NetFlix Watch Instantly, in addition to the few season-3 episodes I saw on Sunday. Based on what I’ve seen, this show stands out, in my view, from other crime procedurals. Because it integrates character and plot more deeply than the typical TV crime drama, for a much more powerful result. And In Plain Sight provides an opportunity to talk about Critical Fandom.

In Plain Sight tells the story of Mary Shannon, an inspector for the Federal Witness Protection Program, as she hides and protects the hunted from their criminal would-be murderers, all while dealing with the insane antics of her flaky, dependent mother and sister. To call Mary’s family “dysfunctional” is an understatement, as is to call Mary herself “codependent.”

As a writer, when I read a book or watch a film or television show, I don’t merely enjoy the experience. Don’t get me wrong: I do enjoy it. But I also think about why I’m enjoying it (or not enjoying it as much as I ought to be). Because if I can understand the why, then I can use those insights to reproduce similar qualities in my own stories. This is what I call “Critical Fandom,” not just reading or watching for the enjoyment, but also for the insight, and I believe it’s a key skill writers should develop.

Here are a few storytelling truths that In Plain Sight demonstrates:

-

Character drives all story conflict. Even in television procedurals! If you’re big on books (and not on TV), a “procedural” is a plot-driven story (external conflict), like a crime mystery, as opposed to a character-driven story (internal conflict), like a romance. One of the big misunderstandings of the fiction writer is that plot drives external conflict, whereas character drives internal conflict. The truth: character drives all conflict, whether internal or external. That is, all story conflict is associated with changes in the way a character perceives his reality. The difference between these two types of conflict is that internal conflict changes how the characters think about their reality, whereas external conflict changes that reality itself.

And as I watch In Plain Sight, I see that the writers understand that every story is a character story, even a crime procedural. It’s not enough that the heros want to figure out whodunnit and save the day; but this urge must come from their character and how they perceive their place in their world.

-

Plot reveals character. This is the corollary to the above. This is “Show; don’t tell.” We don’t connect with characters through what they think or say, but what they do— and how it matches with and differs from what they think, and what they say, and what they say they think.

Interestingly, the guest characters feel deeper than the recurring characters— at first. But after a string of episodes, you start to see subtle patterns in the recurring characters’ behaviors, because each “procedural” storyline helps to build the recurring characters. You eventually figure out that Mary protects federal witnesses so well, because she learned to be codependent by taking care of her dysfunctional family, but that she’s also learned to run from anything that smacks of genuine human relationship. You begin to sympathize with Mary’s sister and mother, at least with what they’re trying to make of their lives. And don’t even get me started on Mary’s relationships with her coworkers.

-

Character is more than just a list of quirks and behaviors, and character change is more than just a random shift in direction. I object to the way some writers of TV procedurals try to inject character into their scripts. They seem to think that revealing character means boring scenes where people talk about their feelings to one another. Or even worse, magical changes in relationships or personalities. Not so! Columbo was full of character, not only in its detective but in its villains as well; and not once did he ever talk about his feelings or change his personality. Columbo was a quirky character, yes, but don’t mistake the quirks for the character itself: his quirks work because they reveal his character, not because they substitute for it.

Similarly, the characters of In Plain Sight have deep pasts, deep needs, and deeply held psychological patterns. Sometimes their patterns help them in meeting their needs, and sometimes they hinder them. These are the qualities that make for interesting characters. Go deep with your characters, way deeper than you think you need to, in order to understand them from the inside out, to understand them even better than they understand themselves.

-

Extraordinary changes require extraordinary forces. If character change is not just a random shift in direction, what is it? The answer: characters change in response to human needs. And the bigger the change, the more powerful the need has to be, and the more critical that need must seem to the character.

Most of the stories of In Plain Sight begin with a character change. A person witnesses a murder or some other crime, and now the criminals and their friends want that person dead. Enter the Witness Protection Program, which will relocate that person and give him a new life, safe from his would-be murderers. Our heros protect that person’s life, but only if he gives up everything he was and becomes someone else. That’s character change, of the most profound.

-

Extraordinary forces produce extraordinary changes. The corollary to the above: whenever a character faces a traumatic event, she’s going to be affected by it. You don’t always have to understand the psychology of that effect, although understanding helps to build a full, self-consistent character.

When Mary was captured and almost murdered by a drug lord (the plot-based, “procedural” story thread), maybe she escaped and was rescued, but her PTSD was only beginning (the character-based story thread). Changes of this sort occur with all the characters, in a layered fashion, with plot-based story threads like building blocks filling out the character arc.

-

Different people meet their needs in different ways. We tend to think of needs in a hierarchy. Our need to stay alive comes first, because if you’re dead, none of your other needs really matter. Then physical needs, like food and water. Then emotional needs, like attention and community and a sense of purpose. But reality doesn’t quite work that way. It is true that we tend to prioritize the fear of being eaten by a lion, for example, over the pleasure we would experience by sharing that lion’s kill. But that applies to any fear versus any pleasure, and if we feel one of our emotional needs slipping from our fingers, that generates fear, too, a fear that might seem even more pressing to us than the physical need to stay alive.

In Plain Sight, because it’s about witness relocation, provides a perfect setting in which to explore these issues. Why would a hidden witness blow his anonymity? Some of the characters do. What’s more valuable than life itself? Lots of things: honor, friendship, affection, status, autonomy.

-

The main characters don’t have to do everything. Most TV procedurals have the main characters doing everything, especially working miracles in fields that they’re completely incompetent at…

… like Mary playing lawyer to her family, friends, and (especially) her witnesses. Oy vey. If she really cared, she’d realize that her duties and competencies are to secure her witnesses’ safety, not to represent them in legal proceedings. But this is what TV procedurals do, because otherwise, they’d have to introduce strong secondary characters, who actually perform an heroic act (at the hero’s behest) and save the day, and that would be wrong on so many levels. But not in my stories, thank you. I prefer tales with characters—even secondary characters—who function realistically and responsibly in their world.

-

Know more than your characters about their world. This not only applies to the characters’ situation, e.g., what’s going to happen when the hero turns that dark corner. It also applies to specialized knowledge in fields that your characters’ lives will be touching. Research, research, research. Pretend you’re writing a scholarly paper on the field, and that after you present your paper, there will be questions from the audience, and you don’t want to look like an idiot.

For example, when Mary’s drunk-driving mother goes to an AA meeting to show the court that she’s serious about dealing with her alcoholism, you the writer have to know that AA is just one of the myriad options available, and that statistically, AA doesn’t keep alcoholics off booze any better than if they just wing it by themselves. And when the court orders her into state-run rehab, which apparently follows an AA-style process— Well, that particular cliché at least might be realistic, because courts in some parts of the country are still very stone-aged about drug and alcohol treatment options. But that presents storytelling opportunities that you shouldn’t let escape. Maybe she fails because of the ineffectiveness of the rehab methods. Maybe the local ACLU chapter takes an interest in her case, because AA advocates a regimen with decidedly religious implications. Of course, that would require a strong lawyer character in a TV crime drama—Gasp!—and we can’t have that.

I’ve been seeing much more, both that excites me and that disappoints me. The difference between character-relevant drama and melodrama. How each story is actually about something, an art I feared was lost with the decline of SF. That heroic characters, no matter how flawed, have heroic qualities, and villainous characters have villainous qualities. How morality (right and wrong) interacts with intent: “good” characters don’t do good out of a need for status or attention, but for spiritual satisfaction (e.g., charity, duty, or even a need to find meaning outside of oneself), even if to dysfunctional extents. And on and on…

Critical Fandom is not about In Plain Sight, because you may not enjoy that show as much as I do. Critical Fandom is about organizing ideas, ways of thinking about what we see that help us to understand the patterns in them. Whatever television, movies, or books you rave over, look deep for storytelling insights that you can use in your own stories.

Keep writing!

-TimK

Leave a Reply